In the recurring dream I have every summer before school starts, I am rummaging in a noisy room. To get a sense of it, evoke the feeling of that classic dream where you forgot to study for the test. Instead, be the teacher who forgot to plan the whole thing, for everyone. I am there, in a classroom, with a class that wasn’t supposed to start until sometime next week. I am in there with a startled and frantic knowledge that I might pull something off, maybe even something great, if only I can

stop

the

noise.

But I am losing them, the volume is rising, the light is bad. I know I have a lesson plan somewhere, something I might use here, in my file cabinet, if only I can find it. I move to speak, but my voice doesn’t carry, like I cannot squeeze my fist. Instead of turning around, I am rummaging. Chairs begin flying overhead.

I wake up wondering why that dream lives in me still. That’s not how I start the year. I curate every first day of a new class like an art installation.

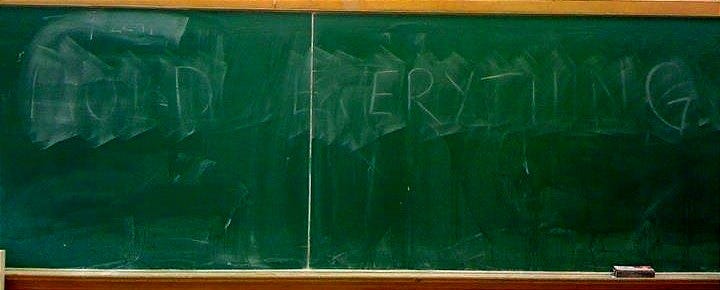

My first year teaching was 2001, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. That classroom had a skyline view of Manhattan on September 11th. I grew up that day, when the towers fell. My teaching career was forged with my numb, naive arms, outstretched beyond what I thought I had in me, trying to hold the young in my care. As for the curriculum that followed, it was this: Hold Everything. Once we got back into the classroom, we studied the world and tried to understand our places in it.

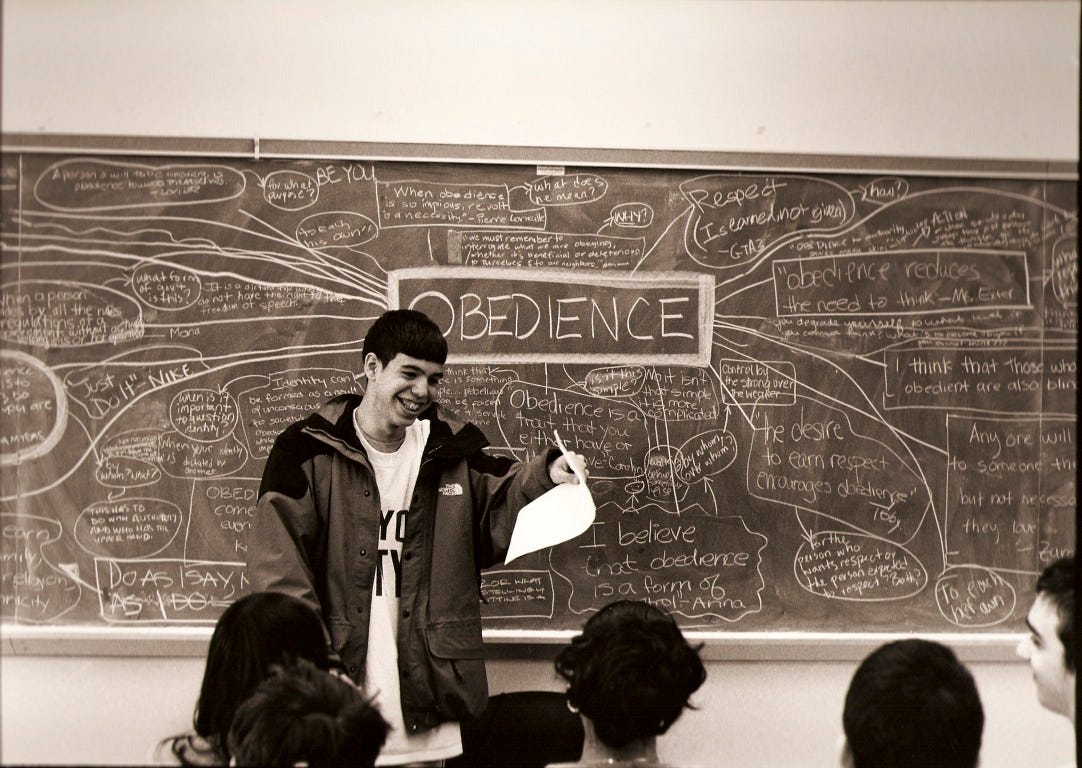

I inherited my file cabinet from my mother, like so many things. The Augusts of my childhood were spent organizing markers in her classroom. This one file cabinet holds thousands of artifacts and big ideas that matter to my mind, papers and notebooks that are precious, actually important pieces of paper. Every June, I sort documents into folders in chronological order, categorized by text: novels, short stories, into eras of history, topics and themes in American Studies. Opening a folder you’ll find photocopies, good sets of beautiful anthologies I made, real slides in sleeves. My philosophy of teaching is to amplify a collection of voices that is not mine, to hold all their gorgeous, contradictory ideas and words in the space; to gather and facilitate.

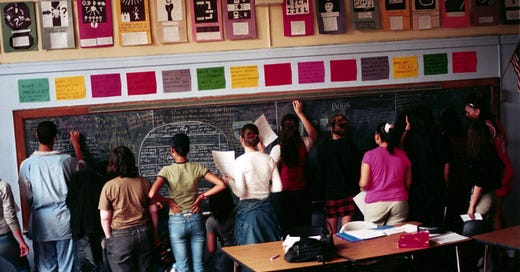

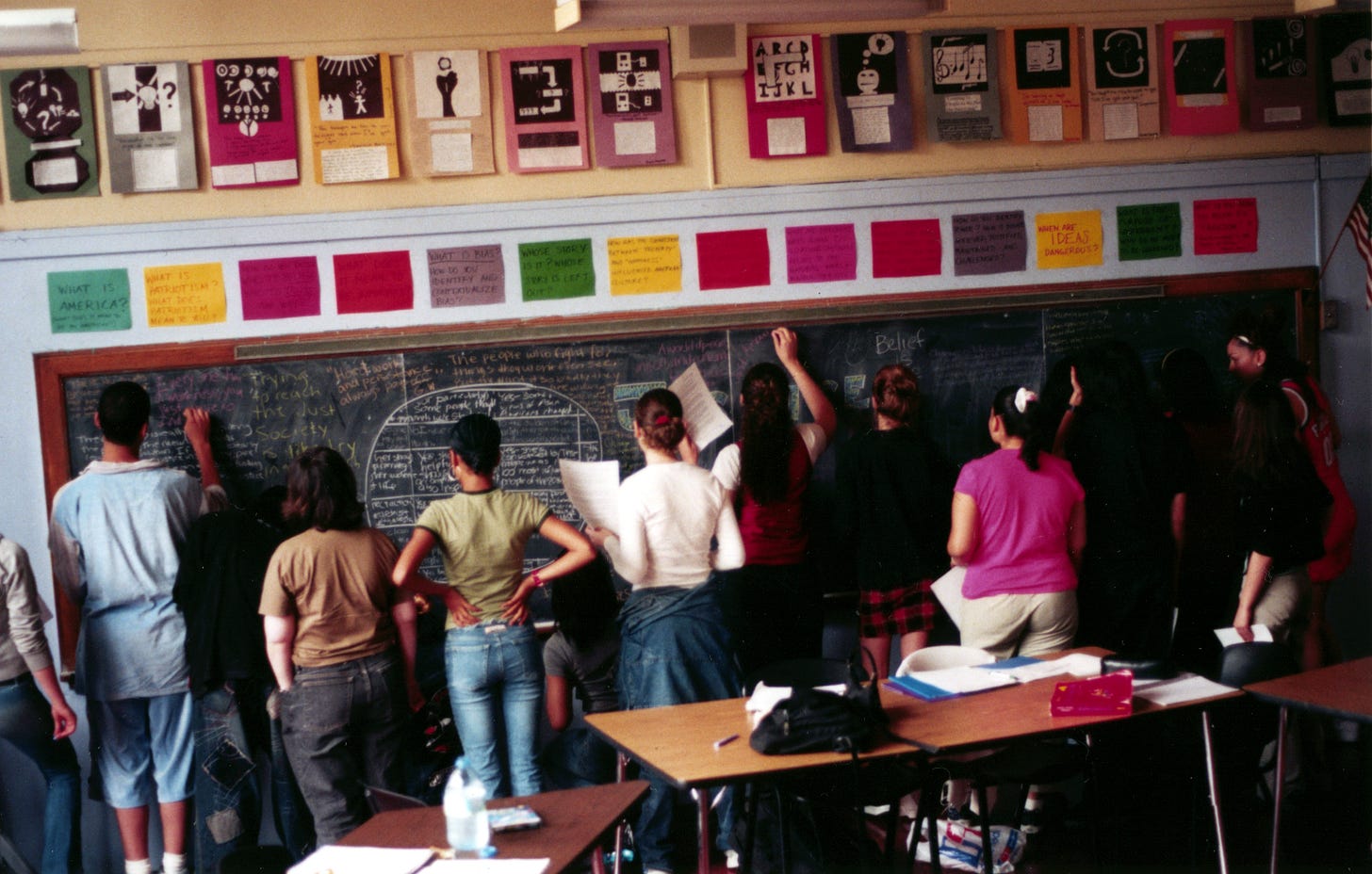

My people are a river of the young who pass through my classroom as they come of age. These words are its rocks and banks and eddies. In the folders are my marginal notes, annotated lesson plans, scrawled pages of notes I take in class to capture students as they dazzle me with their noticings, and I write their names next to their ideas, all of it snaking up the pages. It all means so much to me: the intensity of a discussion, the eye contact, the note-taking, the connection. American Studies gets longer and wider and deeper, and I come to see how little I know. I learn more, the files get stuffed, and old dreams and ideas live on in there, too.

I look backwards and forwards and think: I should probably burn the file cabinet.

Because here I am, clutching the thing I was looking for–yes! I found it! The notes I took about Gettysburg on Hello Kitty Stationary that time, that old mentor’s brilliant, handwritten script connecting the First Amendment to “The Revolt of ‘Mother.’” No. Marie Kondo comes to mind–give it a fond glance, find it quite good, my old curriculum, these friends, and burn it. Because here we stand on a shifting planet with time bound tight, stale ideas threadbare in the 50-mile-an-hour wind. We are so mortal, at scale, now, so mortal. Burn the files for biochar and enrich the soil in my garden with it. Then listen. I eat awkward silences for breakfast. We laugh about that, my students and me. But then, they talk. I’m not saying scrap the content. We must hold a common and complex understanding of the past and its lessons. But we can’t teach it all, not if we are conscious about where we are in space and time as a species on a planet.

In the dream, what’s the worst that could happen if I just turned around empty handed? I had a different dream, and this one only once: I was teaching a huge class in the middle of a busy intersection. Everyone was seated tightly in an awkward circle, surrounded by traffic. I spoke something. The feeling of it was spare and compelling. I asked the right question. I was patient and waited, instead of filling the space. One at a time, their hands rose into the air to speak. In the dream, I sank to my knees in gratitude, my hands outstretched before me, towards them. I began to call on people’s voices as if I were conducting an orchestra. I remember it like a silent film, as pure gesture. This is what it feels like to ask the right question, to hold space.

Public schools are expected to hold everything the rest of society might drop. An essential function of public schools is childcare, or care, generally. In addition to educating our children, schools across New York State provide free breakfast and lunch. Schools provide essential mental healthcare, social spaces, arts opportunities, and athletic seasons that shape people into who they become. Public schools are community hubs with food pantries and playgrounds. For all its flaws, and with notable exceptions, public education protects our young from forced child labor, and educators understand our job is to encourage young people to dream, innovate, and transcend. There are few other places in democratic life where pluralism might look like a way of being, rather than a concept. Critical thinking skills, literacy and democratic citizenship are the practices held by our public schools.

This past Spring I attended a forum of public school students talking about the state of education. The moderator asked those young people: “Can you ask questions about current events in class?” “Does what you learn feel relevant?” They looked at her like they didn’t understand. They slowly shook their heads, no, that does not happen anywhere in my day. It struck me. I thought about my chosen mentors: Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and Dorothy Cotton. These people did not just connect some “real world” to the classroom: they dissolved, they electrified, they reimagined the boundary.

The State of Georgia executed a man named Troy Davis by lethal injection on September 21, 2011. I walked into my classroom that morning and wrote across the chalkboard: Hold Everything. Despite widespread and well-founded calls to stay this execution, Davis’s life was ended in what Amnesty International called “a catastrophic failure of the U.S. criminal justice system.” Davis maintained his innocence until he died. Sometimes a single act, against a single alive thing, clarifies the only conversation and curriculum that matters on a given day. And that day, which is every day, is the day where my students live. They deserve an education that lives there, too.

Dear Bron, I followed a trail on Substack this morning which led back home. You have encapsulated all my hopes for public education: an informed public which reads, listens, evaluates. I based my 30+ years of teaching ESL on Paolo Freire too! How did I not know he was one of your heroes? May we all have your strength and courage in these dark days. Love, Auntie Peg

Damn, what beautiful writing and powerful voice in this piece. Thank you for your service, Bronwen. You and your colleagues are truly protectors, creators, and first responders to our youth.